by CWEARC | Nov 1, 2006

Historically, women in the Philippines held high status in society. We were Babaylans and katalonans (priestesses) then, who were very much revered and involved in the political, economic and social spheres of life. We were also central in the affairs of the clan, in production and decision-making. If there were at all laws or codes to speak of during these times, we were definitely part of the process and the results.

Historically, women in the Philippines held high status in society. We were Babaylans and katalonans (priestesses) then, who were very much revered and involved in the political, economic and social spheres of life. We were also central in the affairs of the clan, in production and decision-making. If there were at all laws or codes to speak of during these times, we were definitely part of the process and the results.

However, this status changed over time as we were influenced and controlled by Islamic laws and the colonial laws of Spain, America and even Japan. The making of laws was irrefutably reflective of our social context and space. For one, the issues of divorce, mobility, and property ownership for women which were recognized during pre-colonial times were radically changed by the Spanish Law that ultimately controlled and placed women in a subordinate position. Basically patterned after the Roman law, we inherit up to this day these biases against women from the Spaniards.

But history has also proven that today’s laws on women have somehow advanced to reflect the real issues and needs of women. The respect for women’s rights was reflected in Kartilya ng Katipunan at the turn of the century. Women’s role in politics has been recognized which is partially attributable to the Philippine suffragette movement. Today’s laws on labor, rape, sexual harassment, sex trafficking, anti-violence against women and many other were results of painstaking advocacy of the Philippine women’s movement.

“A harvest of laws,” is how lawyer Evalyn Ursua, a staunch women’s rights lawyer, referred to laws enacted as a product of the country’s women’s movement. She further asserted that these laws were borne out of the struggles of the women’s movement.

While these laws can be appreciated as concrete gains of the women’s movement, we cannot rely solely on these gains for the defense of women’s rights. For laws are nothing without action. Laws are not always equal to the justice system. Laws become toothless when the powerful and the moneyed class can buy their way out of the many injustices and violence committed against women and children. Worse, laws can be instruments of the state to further degrade and oppress women and children.

Violence against women and children continue to rise despite the existence of these legislation. These laws can be deemed futile for as long as the feudal, patriarchal and bourgeois culture is still very much embedded in our system.

It is for these reasons that the Philippine women’s movement needs to continue its efforts in reclaiming a truly just society, not only through legislative reforms, but through challenging the different social institutions that perpetuate injustice. This can be done through awareness-raising, organizing of women, community consciousness-raising towards prevention of violations and respect and promotion of human rights and women’s rights.

by CWEARC | Mar 8, 2005

Introduction

Introduction

The Philippines is the number one labor exporting country in the world today. As of 2004, there were approximately 8.2 million Filipinos scattered in 182 countries all over the world. An estimated 4,010 Filipino workers leave he country each in search for jobs and greener pastures abroad. In 2004, OFW remittances amounted to US15-16 billion (ILO Data, 2005), contributing almost half of the countries gross domestic product (GDP). The cordillera region has the third highest number of OFWs of all regions in the Philippines, of whom 77% are women.

It is therefore not surprising that the widespread migration of Filipinos to other countries is an issue close to the hearts and stomachs of millions of Filipinos. It is not farfetched to believe that each Filipino family has a relative, friend or acquaintance working abroad. Each day, we hear and face various issues and problems of OFWs in our own homes, workplaces, offices, schools, market, communities, as well as in the media.

Yet, not many of us fully understand the issue of migration and the factors that push Filipinos to work abroad. There are those who still believe that going abroad is due to a high ambition in life, or that it is a trait of Filipinos to be adventurous and to want to see the world. But it is now becoming clear that poverty and unemployment are the main reason for migration- a forced migration of desperate people, who are being sold, commercialized all over the world by our own government.

This research on the situation of overseas Filipino workers from the cordillera was conducted by the cordillera women’s education and resource center (CWERC) in 2002 in order to know more about the actual conditions of women OFWs and their families in the region. Case studies were done in selected communities, secondary date were gathered from government and non-government sources, and documentation of particular cases of individual victims was done, including the toll it has taken on families of OFWs.

The research also aims to present the historical context, which led to the widespread migration of Filipinos, and the role of the government in encouraging such migration. The research further shows that there are major contradictions between the labor export policy (LEP) of government and its professed role to protect the rights and welfare of Filipino migrant workers and their families.

With this issue of Kali on “Filipino Women Migrant Workers: Commodities for Export”, we expose the issue of labor export and forced migration, we sympathize with the many OFWs who are victims of maltreatment, abuse and violence, and salute the millions of migrant workers who are the unsung Filipino heroes of today.

by CWEARC | Jul 1, 2003

Foreword

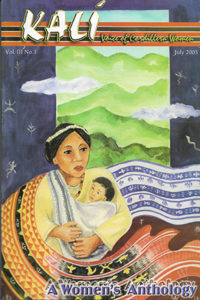

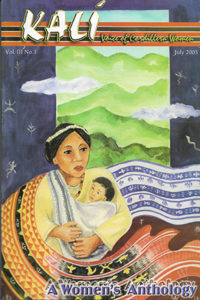

The Cordillera Women’s Education and Resource Center (CWERC) takes pride in announcing the birth of its first anthology of women’s literary and visual arts through its journal KALI. The time is ripe for the unfolding and sharing of women’s creativity and rich interpretation of the various facets of the people’s struggle in the region, and the country in general. The wellspring of people’s literature is the people’s struggle itself.

The Cordillera Women’s Education and Resource Center (CWERC) takes pride in announcing the birth of its first anthology of women’s literary and visual arts through its journal KALI. The time is ripe for the unfolding and sharing of women’s creativity and rich interpretation of the various facets of the people’s struggle in the region, and the country in general. The wellspring of people’s literature is the people’s struggle itself.

Through the years, the women’s movement in the Cordillera has not only continuously developed and honed women activists. It has likewise created a generation of chroniclers not only of the women’s struggle but of the people’s movement as well.

The actual involvement of writers and artists in the struggle for social change is the very material that is immortalized through literature, music and the visual arts. The victorious struggle against the Chico Dam development project was an inspiration to many and continues to motivate women writers and artists to draw parallelisms with contemporary struggles against development aggression. The pain and destruction wrought by imperialist incursion compounded by militarization is etched in the psyche of thousands of women in the Cordillera countryside but through poetry, music and sketches the collective experience is transformed into a sharper and resolute commitment to continue the anti-fascist and anti-imperialist struggle of the militant women’s movement.

A woman organizer is a cultural worker. She joins picketlines and barricades against capitalist exploitation in Lepanto Mines. She treks trails and mountainsides in Dalupirip, Itogon or the remotest sitio in Kalinga and Abra to understand the myriad issues and situations. To be able to motivate other women and the rest of the oppressed and exploited masses to get involved and act for their themselves entails a painstaking process of touching the consciousness and the spirit. Thus capturing through poetry, songs and colors the issues and problems that ail the people becomes an instrument in heightening awareness, arousing the reader or audience to take action.

The anthology showcases Cordillera-based women writers and artists. But a section has also been assigned to other writers and composers outside the region whose words embody the principles and aspirations of the militant women’s movement in the region.

This anthology is for all the people who tirelessly give the women’s movement the inspiration to pursue the struggle and the vision for a truly free and democratic society. And this shall not end here. The anthology of the people’s struggle is voluminous. This is but an initial contribution.

by CWEARC | Jun 1, 2001

Introduction

Introduction

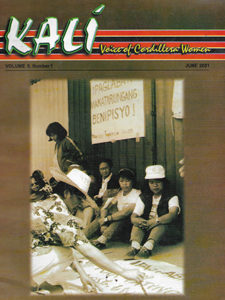

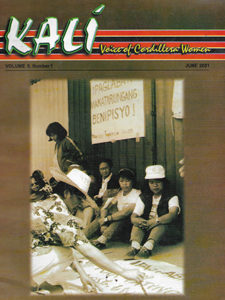

Women workers are among the most hardworking and productive forces in Philippine society. They work for many hours on end, in factories, firms, service establishments or plantations, in order to produce commodities and services from which capitalists earn their profits. Yet they can be said to be among the most exploited, hardly earning enough for their own and their families’ subsistence. They receive meager wages, usually below the legally mandated minimum wage, are often deprived of the benefits to which workers are entitled, and are denied their rights as workers to job security and to self-organization. In addition, they are discriminated against and oppressed as women, victims of a society which views women as inferior beings, as objects of entertainment, and as subjects of domination.

This second issue of CWERC’s journal KALI: Voice of Cordillera Women brings to you the situation of the women workers in the Cordillera today. It features women workers in two factories in the Baguio City Export Processing Zone where labor contractualization has become not just a trend, but the norm among the foreign-owned companies in the zone.

As understood by many, labor contractualization refers to the temporary or short-term work by a laborer. Thus, a contractual worker is one who has no regular work and has no security of tenure. As a contractual worker, he or she is denied the wages and benefits of regular workers. He or she receives lower wages and no benefits, thereby increasing the rate of his or her exploitation.

Labor contractualization has many forms and faces. It is seen when workers are considered as contractuals, casuals or apprentices when in fact they do the work of regular workers. It occurs when contractual workers are directly hired by the capitalist or are agency-hired by a labor-only contractor. Or when the employer is a subcontractor or concessionaire, his workers are contractuals and are paid daily, per piece or for every job order. Then you can have contractual workers or “permanent casuals” who are still considered casual workers despite having worked for more than the legally required 180 days to become regular workers.

Labor contractualization negates almost all the labor laws and policies which have been won through long, bitter and bloody struggles of the workers throughout our history.

It allows capitalists to relegate workers to a position of enslavement by depriving them of job security and of all the rights of workers. It therefore has the overall effect of pulling down the wage level of the whole working class.

The research and case studies of labor contractualization presented here, give us a graphic illustration of the plight of women contractual workers and the hardships they have to endure. They portray the image of the woman worker: exploited yet resilient. Oppressed yet struggling for the well-being and dignity she deserves.

by CWEARC | Aug 8, 2000

Introduction

Introduction

“KALI” is a local term of the indigenous kankana-ey people of the cordillera region, Philippines. It means to speak to talk. It also means to speak the dialect or language of the people.

“KALI” now comes to you as the journal of the cordillera women’s education and resource center (CWERC), back after some years of relative silence. We offer this journal as a voice expressing the various concerns of women in the cordillera, in the Philippines, as well as in other part of the world. It aims to present in depth the effort of cordillera women to understand their situation and to position themselves within the broader social realities. It deals not only with the particular concerns of women but with general issues that impact on women in particular ways.

It is clear from the start that our standpoint is in the interest of grassroots women belonging to the oppressed classes and sectors, particularly the peasant, workers, and semi-workers, youths, professionals and small business, indigenous peoples, lesbians and migrant workers. Particular focus and highlights will be given to the struggles of these women who have to deal with threats to their survival from day to day. We see their struggles and their victories as a significant contribution to the general cordillera women’s movement for national democracy, self determination and equality. May they serve as an inspiration for the millions of women around the world working for real change.

At this point in our history, it is with deep concern that we regard the situation of the indigenous peasant women in the cordillera. At the outset, cordillera indigenous peasant women experience multiple layers of oppression and exploitation – as peasants, as women and as indigenous people. They are subjected to various aspects of feudal and semi-feudal exploitation in the farms on which they toil for many hours. They experience forms of gender oppression within indigenous as well as imposed socio-political structures and institutions. They suffer discrimination and national oppression in violation of the indigenous people’s rights to self determination.

The push towards globalization and liberalization of trade has aggravated the situation of the indigenous peasant women. Policies and programs prescribed by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank and the international monetary fund have resulted in the displacement of indigenous peoples from their land, undermining their subsistence agricultural economies and weakening their indigenous culture. This has led to a host of other problems for the indigenous women such as poverty, unemployment, trafficking, abuse and others.

The San Roque Multipurpose Dam Project located in Pangasinan, Philippines is one such project designed to keep in line with the development paradigm of globalization. Natural resources, in this case san roque dam, backed t Agno River and its eco-system, are exploited by multinational corporations for their own profit and interests. The Japanese and American investors and funders of the San Roque dam, backed by the Philippine government under the administration of President Joseph Estrada, are ramming through with the controversial dam project. This, in spite of our sorry experience with the Ambuklao and Binga Dams along Agno River, the considerable adverse impact of mega dams on affected communities and the environment, the lopsided and onerous terms of the contract entered into by the National Power Corporation with the San Roque Power Corporation and despite the broad and militant people’s opposition to the project.

This issue of KALI features the San Roque Dam and the various aspects of the issue. Although no purely an indigenous peasant women’s issue, the San Roque dam is an urgent concern for all of us because it poses a threat to the survival of Indigenous and peasant communities in the Cordillera and in Central Luzon. We call your attention to this serious problem and urge you to be a part of the broad people’s movement against the construction of the San Roque Dam.

Historically, women in the Philippines held high status in society. We were Babaylans and katalonans (priestesses) then, who were very much revered and involved in the political, economic and social spheres of life. We were also central in the affairs of the clan, in production and decision-making. If there were at all laws or codes to speak of during these times, we were definitely part of the process and the results.

Historically, women in the Philippines held high status in society. We were Babaylans and katalonans (priestesses) then, who were very much revered and involved in the political, economic and social spheres of life. We were also central in the affairs of the clan, in production and decision-making. If there were at all laws or codes to speak of during these times, we were definitely part of the process and the results.

Introduction

Introduction The Cordillera Women’s Education and Resource Center (CWERC) takes pride in announcing the birth of its first anthology of women’s literary and visual arts through its journal KALI. The time is ripe for the unfolding and sharing of women’s creativity and rich interpretation of the various facets of the people’s struggle in the region, and the country in general. The wellspring of people’s literature is the people’s struggle itself.

The Cordillera Women’s Education and Resource Center (CWERC) takes pride in announcing the birth of its first anthology of women’s literary and visual arts through its journal KALI. The time is ripe for the unfolding and sharing of women’s creativity and rich interpretation of the various facets of the people’s struggle in the region, and the country in general. The wellspring of people’s literature is the people’s struggle itself. Introduction

Introduction Introduction

Introduction