by CWEARC | Dec 15, 2023

INTRODUCTION

The Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) underscores that “most people infected with the virus will experience mild to moderate respiratory illness and recover without requiring special treatment, while some will become seriously ill and require medical attention. Older people and those with underlying medical conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, or cancer are more likely to develop serious illnesses. Anyone can get sick with COVID-19 and become seriously ill or die at any age.”

The first suspected case in the Philippines was investigated on January 22, 2020, involving two Chinese nationals on vacation in the country.2 Barely Four months later, the first known Covid positive case in the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) was reported in May 2020—an overseas Filipino worker who arrived from the United Arab Emirates in his hometown in Manabo, Abra.3 By November 11, 2021, the Department of Health Cordillera Center for Health Development (DOH-CHD) had reported a total of 92,221 Covid positive cases in CAR, with Benguet province having the highest number of active cases at 940.4 Disaggregated data according to sex is not available from official government records.

While it is true that the impact of the pandemic cuts across individuals from all walks of life, COVID-19 disproportionately affects the poor and vulnerable, including Indigenous peoples, women, and children,5 with wellbeing, poverty, and hunger being core issues related to COVID-19’s impact. The Philippines was already among Asia’s poorest countries even before the pandemic. Towards the end of 2020, a quarter of Filipinos were living in poverty, surviving at USD 3 per day according to the World Bank.

In this light, the research explores the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on women in the Cordillera region, Philippines. Specifically, the study investigates reproductive health, food security and nutrition, mental health, gender relations, and culture based on existing knowledge and literature, observations, and expressed community needs. Knowledge gaps exist in observations and anecdotes, necessitating documented knowledge to address expressed and observed community needs. In addition, the research scrutinizes socio-political issues surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been leveraged for control. Finally, we want to unravel other dimensions of wellbeing encountered during the research process.

In this study, we align with the WHO definition of wellbeing as “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” We particularly explore the disparate impact of the pandemic on women’s wellbeing, as it influences both the family’s wellbeing and the roles of women-both traditional and contemporary-in both family and society. The research focuses on the Cordillera region, home to Indigenous peoples belonging to 7 major ethnolinguistic groups collectively known as the Igorot (people of the mountain) Indigenous peoples. The Cordillera population is presently at 1.7 million, 48% of whom are women, or 100 women for every 104 men, according to latest data of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

We capture the nature of the socio-economic aspects of COVID-19’s impact on women through the narratives of the participants in key informant interviews and focus group discussions.

To request for your copies, please send us a message at cwearc@cwearc.org.

by CWEARC | Jul 25, 2022

The following advocacy publications by CWEARC are still available:

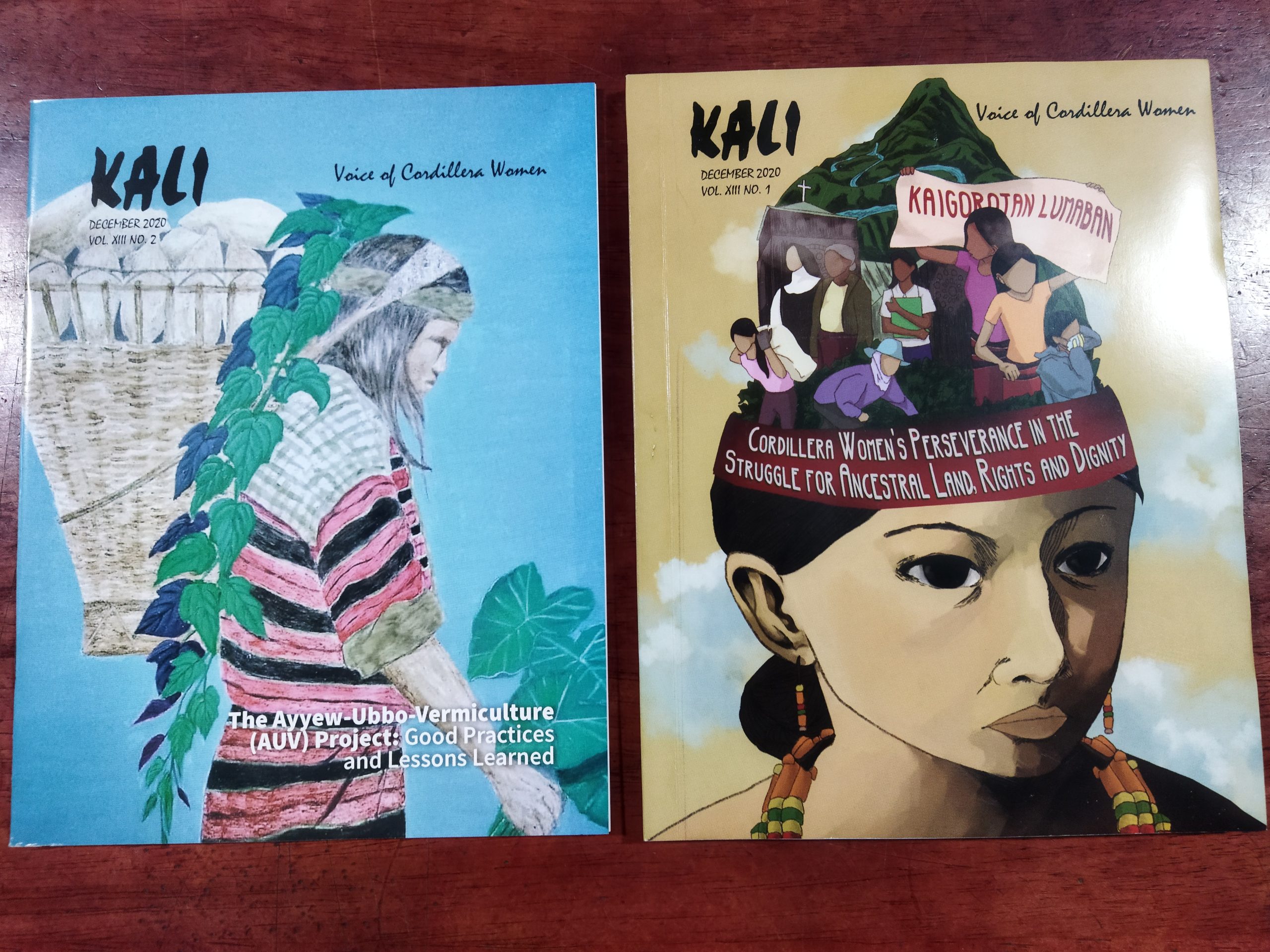

Kali: Voice of Cordillera Women (Volume XIII No.1, December 2020). Cordillera Women’s Perseverance in the Struggle for Ancestral Land, Rights and Dignity (A Women’s Anthology of Poems, Songs and Stories)

Kali: Voice of Cordillera Women (Volume XIII No. 2, December 2020). The Ayyew-Ubbo-Vermiculture (AUV) Project: Good Practices and Lessons Learned

To request for your copies, please send us a message at info@cwearc.org. Copies are also available at the Indigenous Peoples Center near Burnham Park. We are happy to contribute copies to libraries in schools and universities.

by CWEARC | Dec 1, 2018

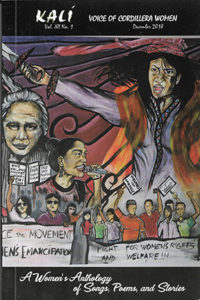

Editor’s Note

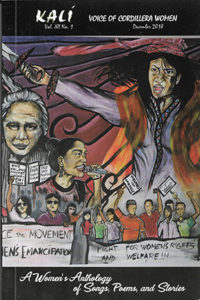

It has been fifteen years since the publication of the first volume of KALI, Voice of Cordillera Women. The first anthology echoed the Cordillera women’s recollection of the early struggles and their tributes to the victories of the pioneers of the Cordillera people’s movement, such as the participation of women against the Chico Dam and Cellophil Resources projects, and the ensuing burning issues of the early 2000s. The corruption and tyranny of the regimes that manifested as development aggression and militarization in the region were denounced by women writers, visual artists and musicians and they found their voice in Kali.

Much has transpired in the women’s movement in the Cordillera through those years from which we draw valuable lessons and insights. This trove of experiences and challenges has been translated into individual writers’ reflections and leaps; and collective dedication of communities and women’s organizations to the continuing pursuit of the aspiration of the women’s movement. Because development aggression still rears its ugly head and tyranny has fiercer fangs that preys on women, defense is much bolder now.

Women organizers in the indigenous people’s movement, women who work as staff in development programs, women who are mothers and income earners in communities, students who carry out cultural work in schools, have crafted their literary pieces, songs, stories, visual images as mirrors of their daily lives and involvement in the struggle for a better, humane society. Their aspirations are for a Cordillera and a country that practice and enjoy the fruits of self-determination in aspects of politics, economy and culture. In this period under a regime that spites human rights and reeks of misogyny and disregards the value of life, how is rage expressed by women who are not only the life source but also nurturers of generations? In this period of utmost deprivation and wanton disregard for right to life and security, how is resistance expressed by women who dare not remain on the sidelines but also take crucial tasks in the front lines? Women draw strength and courage from the heroism and selflessness of foremothers and ancestors who were not superwomen, but were able to combat fear, limitations and real enemies. The power to create, to transform, to reflect and act, to leave and break from the shackles of tradition and social limitations is a weapon that women in the Cordillera are learning to protect and utilize. The beauty is in the realization that they are validated by their fellow women in these perilous times, and supported by men who have deep understanding and appreciation of the women’s struggle. It is time once again to share the voice of Cordillera women to wider communities of readers. The poems, songs, personal essays and illustrations in this anthology are testimonies that we shall prevail, we shall not be daunted to express our fears and aspiration until true change has come to our Motherland.

by CWEARC | Jun 1, 2016

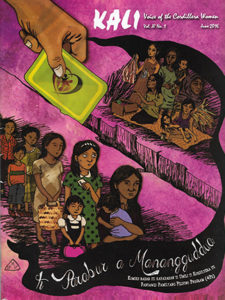

Pakauna

Daytos a komiks ket naglaon kadagiti istorya ken kapadasan dagiti nainsigudan a babbaie iti rehiyon Cordillera maipanggep iti Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT), wenno popular iti termino a 4Ps (Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program), a kangrunaan nga ipagpagna ti Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD). Nagrugi ti badyet na daytoy iti P4 milyon idi 2007 para iti 6,000 a benepisyaryo.

Daytoy ti kangrunaan a programa nga ipanpannakil ti dua a nagsaruno nga administrasyon (Gloria Macapagal Arroyo ken Benigno Aquino III), a mangrisut kanu ti kinakurapay dagiti umili a Pilipino. Ti kangrunaan a pokus ti 4Ps ket para iti edukasyon ken salun-at dagiti pamilya a napili.

Ti 4Ps ket inadaptar ti Pilipinas babaen iti duron ti World Bank (WB) ken Asian Development Bank (ADB) a kangrunaan a naggapuan ti pondo. Immuna a naipadas daytoy a programa idiay Latin American ken Africa sakbay nga inadaptar dagiti gobyerno iti Asia, mairaman ti Pilipinas. Sigun iti panagadal iti kapadasan ti Latin America ken Africa, maysa daytoy a dole-out; programa a nangiyaw-awan kadagiti pudno a pangkasapulan ti umili a nabayag nga inlablaban da kas iti pudno a reporma iti daga ken agrikultura, natalged a pagtrabahoan, ken naan-anay a sweldo.

Daytoy a komiks ket nakabasar kadagiti istorya manipud kadagiti workshops ken focused grouped discussion kadagiti babbai idiay Kalinga, Apayao, Montanyosa, Abra ken Baguio manipud idi 2012. Ti inisyal a report, “The Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) in the Cordillera from the Perspective of Indigenous Women” ket naipresentar idi naisayangkat ti Cordillera Development Conference idi Nobyembre 2013. Ti Proceedings ti komperensya ket naiparuar. Napabaknang ti inisyal a report babaen iti nagtultuloy a dokumentasyon kadagiti kapadasan dagiti benepisyaryo ken saan a benepisyaryo iti 4Ps.

by CWEARC | May 1, 2015

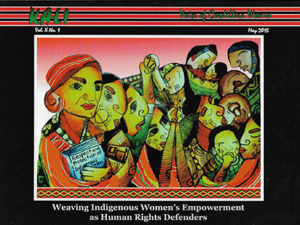

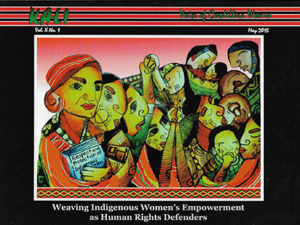

Foreword

It’s not completely a new initiative. What makes this journey unique, however, is the utilization of positive aspects of customary institutions and values as avenues to promote indigenous women’s rights. It was a painstaking journey of human rights awareness and capacity building of indigenous women in 26 communities of Sagada and Bontoc, Mountain Province in the Cordillera region and in the municipalities of Alabel and Malapatan in Saranggani Province in Mindanao, from the last quarter of 2010 to 2013. It was an empowering experience for the participants who face human rights issues and violence against women due to conditions of militarization, development aggression, and poor delivery of social services. Development aggression in the form of corporate mining and energy projects is an issue of economic violence among indigenous women participants deprived of their access and control to land and natural resources. That empowering journey pushed them to speak and practice human rights as a collective, broke their silence about their own experience of sexual and domestic violence and mustered their confidence to access facilities and services that reduce their vulnerability to violence.

Their human rights awareness was not theirs alone. The indigenous women participants shared that awareness to their communities who became their support to access certain services and entitlements. The awareness was translated into having the skills to communicate human rights to fellow women within their organizations and communities, and to structures of leadership and decision-making.

There is now a deeper appreciation of having written documentation of their own experiences from the usual practice of oral tradition. The stories of the participants that they themselves have written are proof of how liberating the journey was. Their stories show were changes have occurred– in the mind-sets, attitudes or behavior, and in practice. These changes are difficult to measure. However, these powerful stories make the transformation more concrete.

This report also clarifies the role of customary institutions in protecting women from violence, and how women are respected traditionally. With the decline of power of indigenous socio-political institutions brought about by the dynamism in the wider society that indigenous peoples are very much integrated into, the protection or values that used to be accorded to women has eroded. It is vital to accord value on efforts made by organizations of indigenous women and communities in strengthening and promoting positive aspects of indigenous systems that provide protection for women against violence and danger.

Where there is a growing conflict between human rights and business, a larger gap between human rights holders and duty-bearers is created. Nothing would sustain the empowerment of women but their continued interest and collective actions to be liberated as productive members of their communities and the wider society.

by CWEARC | Jun 1, 2014

Years before, the winds in Sagada gave off the sound of rustling pine needles, the wings and songs of birds, and the fresh smell of the forest. Hardly did anyone think that soon enough, the wind would bring with itself the metallic sound of the spinning turbines of a wind farm.

Hardly anyone thought that it would bring the sound of heavy machinery drilling and digging, the sound of the earth being savaged in the name of progress, the sound of trees falling, and the stench of chemicals spilling. Hardly anyone, except for PhilCarbon president Ruth Yu-Owen and her supporters. PhilCarbon and the SagadaBesao Windmill Corporation drew up plans to build windmills on a windy ridge in the boundary of Sagada and Besao in Mountain Province. The proposed wind farm would have up to 15 wind turbines along the PilaoLangsayan Ridge. Each turbine would produce 600 kilowatts, totalling 15 megawatts of electricity. Mountain Province consumes only five to six megawatts. One of the selling points is to sell the excess nine to ten megawatts produced by the wind farm to electricity grids in other places in Luzon.

One process that any development project undertakes is an Environment Impact Assessment by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. In addition, the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) provides that projects like the wind farm should include an assessment of how it will affect the indigenous people and natural resources in those areas. However, projects aiming towards so-called development have hardly ever taken into account the rights, livelihood, and culture of indigenous communities.

The windmill turbines were designed to be 80 feet tall, with rotor blades of 40 meters long. These turbines will be built near sources of water that will be inevitably and negatively affected by construction activities. The rotor blades will destroy the surrounding trees. The target project area also serves as a pastureland therefore will disturb the livestocks. Equally, the project will disrupt the routes of migratory birds. Imagine the mountains.

Imagine the pine trees. Imagine the monstrous metal turbines, starkly white and lifeless against the backdrop of the forest green.

PhilCarbon and its proponents promised that the affected municipalities would divide between themselves a royalty of one centavo for every kilowatt the wind farm produces. A fraction of a centavo per kilowatt, in exchange for the destruction of the land and its resources, and for the disruption of the natural course of living things that reside in the area. Obviously, the generosity of PhilCarbon knows no bounds—except for the bounds of profit.

Meanwhile, in Sabangan, the Chico River was despoiled by the construction of Hedcor’s facilities. Chico River has been the site of development and military aggression for years—it calls to mind the martyrdom of Macli-ing Dulag, who was murdered in his own home for the sake of “progress”. Hedcor is building a “mini” hydro power plant in Barangays Napua and Namatec. Testimonies from affected communities say that efforts of Hedcor to prevent damage to the river have been ineffective. They also speak about the deceptive moves of Hedcor. Instead of a mini hydro power plant that produces only 14 megawatts, Hedcor is actually building a power plant that would produces a total of 55 megawatts—far from the 14 megawatts they first claimed to build.

There are numerous renewable energy plant applications in Mountain Province alone. BIMAKA is planning on building a series of six mini hydro projects along the Balas-iyan river in Besao. All in all, there are 11 hydro-electric projects outlined in Mountain Province. The MainitSadanga geothermal project of the PRCMagma Energy Resources Corp., which is a partnership with Chevron expected to generate 80MW will be affecting a wide span of land in Bontoc and Sadanga of Mountain Province. Leaders of indigenous women’s organizations in Mountain Province say that energy projects are needed for other investments in the province especially mining and tourism.

Imagine a map of Mountain Province littered with markers for mining and renewable energy applications.

With destructive mining and renewable energy applications come militarization, harassment, and various other human rights violations. In Sagada, when the Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) assembly held for the indigenous communities affected by PhilCarbon’s windpower project was conducted, the 54th IB under Colonel Martinez also had their operations. In Tocucan, indigenous leaders that opposed the mini hydro power plant project were harassed by members of the CAFGU1, a paramilitary group.

PhilCarbon also disseminated misleading information regarding the schedule and nature of the FPIC assemblies. Personnel of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) who are mandated to uphold the rights of indigenous peoples, were party to PhilCarbon’s deception and manipulation of the FPIC process.

Despite all this, the affected communities especially the women, took action to uphold their rights and to protect the natural environment of their homeland. A 100-meter tall anemometer tower that tests wind speeds was built by PhilCarbon in preparation for the wind farm project in Sagada. On June 5, 2013, the structure that costs Php 1.5 million was felled by anonymous members of the protesting communities.

All over the communities affected by energy projects, the women actively participated in study meetings on issues regarding these projects, and made sure to attend every assembly called by the NCIP in order to voice their opposition to the destructive projects. In Tocucan, the women conducted a petition signing against the hydro project, and attended consultations in order to personally voice out their protests. The necessity to act and prevent the corporate energy projects is a demonstration of how women value life and the source of life which is the land. For them, it is upholding the dignity of women and peoples to respect and uphold life of present and future generations. Young women leaders say that violence against women is addressed in their

empowering participation to these struggles. The leadership they develop earn the respect of their communities. It raises their profile as women.

Now, imagine the struggle of the communities affected by the megadam project along Chico River during the Marcos dictatorship. Imagine the women—mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters—who confronted troops of soldiers during that struggle. Peoples of the Cordillera have shown, time and again, that we will stand together in order to protect our land, life, and resources.